The results of a new study from the IEO in Milan lay the groundwork for an effective combined treatment against the most formidable of the “big killers.” The development of a therapeutic vaccine is also closer.

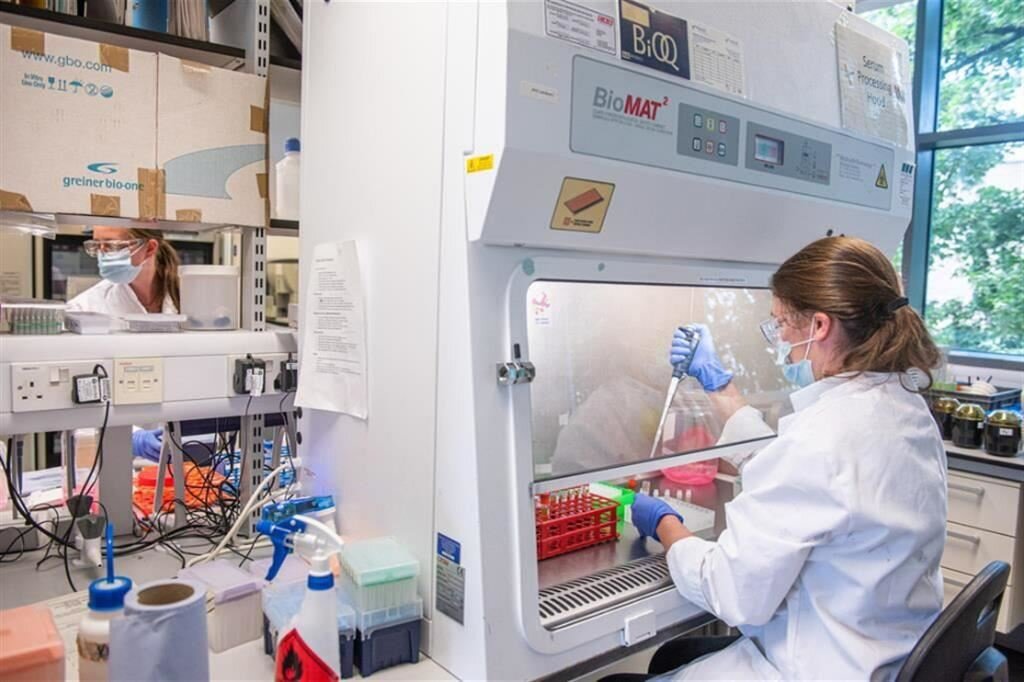

What if the solution to cure pancreatic cancer lay in the previously unknown synergy between two drugs? Even better, between a drug already on the market and immunotherapy? This is the hypothesis followed by researchers at the European Institute of Oncology (IEO) in Milan, which has led to “surprising effects,” just described in Science Advances. Essentially, the research group coordinated by Gioacchino Natoli has discovered the molecular mechanism by which two therapies used for this disease—which, by 2030, will become the second leading cause of cancer death—are individually not very effective but, when combined, have shown in preclinical models the ability to achieve effective tumor control: these are trametinib combined with immunotherapy.

Therefore, the surprising and now legendary resistance of pancreatic cancer could soon waver. Against this true “big killer,” whose ten-year survival rate has remained unchanged over the past half-century, science—with Italy at the forefront—has launched a powerful offensive that is finally beginning to yield significant results. Only 20 days ago, the IEO, in collaboration with two other prestigious Milanese research centers, the Humanitas Institute and the IFOM (Fondazione di Oncologia Molecolare), and with the support of the Airc Foundation, published in Cancer Cell a study that led to the identification and detailed characterization of the profound heterogeneity of each individual pancreatic carcinoma analyzed, thus revealing how this very heterogeneity substantially contributes to the ineffectiveness of existing treatments, and outlining possible new therapeutic approaches also with the aid of artificial intelligence.

Today comes a further step forward against a disease characterized by a set of very well-defined DNA mutations, such as that of the Kras gene. Against such mutations, some targeted molecular drugs have been tested but have so far not produced the expected therapeutic results. Hence the need to go further. “We used advanced genomic and computational analysis procedures,” explains Natoli, “to determine the reasons for the resistance of pancreatic carcinoma cells to trametinib. This analysis showed a surprising effect: even though trametinib does not significantly slow the growth of tumor cells, it activates mechanisms that can make them targets of an immune response. Based on these data, in collaboration with Andrea Viale’s group at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, we evaluated in preclinical models the therapeutic effect of combining trametinib with drugs that enhance the immune response against tumors, the so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors, obtaining significant therapeutic effects.”

Italian scientists have also discovered that portions of ancient viral DNA, essentially endogenous retroviruses dating back hundreds of thousands or even millions of years, silenced in the human body and essentially inert, if activated, simulate a viral infection. And the cells that express them are detected by the immune system just like cells infected by current viruses. Consequently, the IEO specifies, the immune system reacts by attacking the tumor cells expressing endogenous retroviruses, thus destroying the tumor. “This new approach paves the way for a rational combination of treatments that could prove very effective in fighting pancreatic cancer. Moreover, the activation of endogenous retroviruses induced by trametinib could provide new targets for the development of therapeutic vaccines against pancreatic cancer as well. Now we need confirmation of the data obtained in the laboratory in upcoming clinical studies, which we hope to launch as soon as possible,” concludes Alice Cortesi, first author of the article.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE LINK: https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/pancreas

REGISTERED OFFICE AND PHONE

E-MAIL AND PEC

SOCIAL

Via Maestri del Lavoro 5

Pescara

65125

2018-2023 © All rights reserved

C.F. 91145270681

Medicine. Pancreatic cancer: surprising effects from targeted drug plus immunotherapy

Medicine. Pancreatic cancer: surprising effects from targeted drug plus immunotherapy

2024-04-10 08:36

2024-04-10 08:36

Array() no author 88942

REGISTERED OFFICE AND PHONE

E-MAIL AND PEC

SOCIAL

Via Maestri del Lavoro 5

Pescara

65125

2018-2023 © All rights reserved

C.F. 91145270681